Introduction

A little more nature for our society – that‘s what the iteratively shaped, fungi-based luminaire Hy.le is aiming for. The reflector consists of a composite that has grown naturally from wood waste and the mycelium of mushrooms. With the aid of the small “flashlight”, the design is intended to encourage exploration, highlight the unique aesthetics, create fascination, promote discourse, and ultimately take away the myth surrounding these essential organisms.

Institute

Hochschule für Angewandte Wissenschaft und Kunst HAWK Hildesheim Fakultät Gestaltung

Student

Maurice Lötel

Support

Julia Kuhlenkamp (Werkstattleitung Modellbau)

Bernd Krupp (Werkstattleitung Licht-/ Elektrotechnik)

Supervision

Prof. Dr. Sabine Foraita

Prof. Dr. Manuel Kretzer

Material

But what exactly is mycelium? And how does it allow to create composites with practical use?

The term mycelium refers to the substance of fungi, whether in the form of the visible fruiting body (which is often colloquially referred to as a “mushroom”) or the root network located in the substrate. You can draw the comparison to a carpet: The entire fungus consists of a meshwork [the mycelium], which in turn consists of individual, very fine filaments [the hyphae]. And exactly therein lies the peculiarity, because unlike a carpet, these hyphae do not have to be aligned but have the ability to anastomose. This property, which the blood vessels in our bodies also possess, describes the literal growth of cell structures through each other. Thus, when the fungus spreads, the hyphae penetrate the to-be-digested matter and themselves on a cellular level. The resulting compound can no longer be separated and is therefore very resistant.

However, in addition to suitable environmental conditions, this process also requires a nutrient-rich substrate that should be adapted to the fungal species to be used. The fungus used in this project is Ganoderma lucidum. Also known as Reishi, it has been considered a medicinal and vital mushroom for thousands of years and has been studied specifically in regard to the production of mushroom materials. In addition to its compatibility with humans, it is especially known for its extremely homogeneous, fast and densely growing mycelium, which predestines it for the production of solid materials. Since this fungus grows on hardwood, the use of economic hardwood waste seemed optimal.

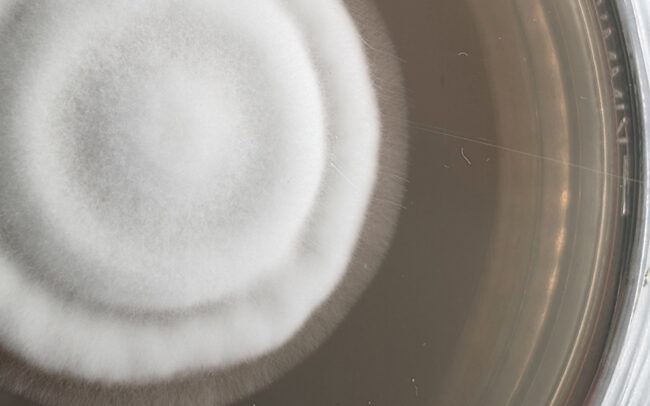

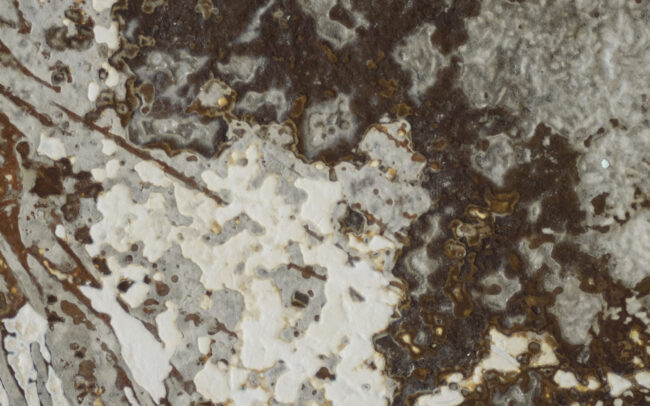

This not only opens up the use of otherwise unused tree componentsm such as smaller branches, but also enables the utilization of regional resources – in this case beech wood, which is widespread in Germany. The process is very simple: The wood waste is brought to a desired grain size, cleaned as best as possible (preferably sterilized), and then inoculated with the fungus. If suitable environmental conditions are given (especially around 20 °C and at least 60 % moisture content within the substrate), the fungus grows completely through said substrate within a few days. Due to the very fine but “chaotic” structure of the hyphae, all particles are connected, even the smallest gaps are closed, and potential negative molds are filled with a high degree of detail. After about a week, the composite is already stable enough to be removed from those molds and to form its mycelial skin within a few more days. This is a kind of protective layer of the organism, that forms on air-facing surfaces and ensures that the interior (of the substrate-fungus composite) does not dry out. In addition, it is also aesthetically interesting because it starts out almost pure white and very homogeneous, but can be manipulated in shape and color by various influencing factors.

Design

Why actually a luminaire?

Since mushrooms are something unknown to many people, often even associated with illness or disgust, an object was to be created that would stimulate and normalize the (physical) confrontation; in other words, getting used to these organisms and, with that, bringing “light into the darkness”. As mentioned in the beginning, the aesthetic layer was intended for this purpose since it doesn‘t require certain knowledge about the topic and can generate profound fascination.

In addition to a market analysis, experimental discussions regarding the production of composites and the evaluation of suitable electrotechnical components, models of various kinds were developed, which further concretized the design. The elaboration of those models ranged from sketches and digital variants to model construction from styrofoam and the implementation on the basis of beech wood and Ganoderma lucidum. The technical components have been designed to be as energy-efficient as possible and with the use of a small LED lamp in mind.

After several iterations, a direct reference to the natural model was finally established: A Fomes fomentarius growing on a tree trunk. With this principle of biomimicry, that is, the use of nature as a universal inspiration, as well as the sustainability idea “As much as necessary, as little as possible.”, this natural arrangement was then geometrically reduced to a minimum and transferred into the stylistic elements of the luminaire. The focus, as described above: Staging the composite. Every other component‘s purpose is to fade into the background or to highlight the composite reflector.

Culture (embodied here by the technical, dark components) can help nature to realize its potential and, through its contemplation, can provide new learning that enriches one‘s life, generates fascination and stimulates innovation. The circle plays an important role in this; both semantically and in terms of form, it is considered harmonious, neutral, „perfect”, but also infinite.

In a hands-on situation, interested individuals are introduced into a whole new little world. They can pick up the “flashlight” and go on an expedition, literally illuminating the object from all sides and experiencing the always uniquely grown relief. This uniqueness lies in the previously mentioned mycelium skin, which is able to protect the organism even better from the environment with the help of so-called demarcation borders. Through the incorporation of pigments, a repellent border is drawn that reflects the substrate used in its coloring and can be influenced accordingly – both with the help of the substrate, as well as time and, above all, the intensity of exposure to water and air. Their color progression usually begins with soft beige tones and, within a few days, can turn yellow and red tones, to a dark brown or even black.

Potential

Fungi-based composites, such as the one described above, initially tend to have foam-like properties – they are generally slightly more brittle but, to some extent, hydrophobic and fire-resistant. Starting as a thermal insulation material, they are finding ever broader applications in the manufacture of acoustic components and furniture, can be processed in many different ways, and are 100 % biodegradable. Even the production of a mushroom leather consisting directly of the mycelium is already in an advanced phase. In addition, fungi (including bacteria) can be used to produce proteins and vitamins for the food industry or even result in biodesign. With the help of the anti-inflammatory effects of many fungi, it may be conceivable, for example, to produce clothing that supports wound regeneration. Either way, fungi are extremely fascinating organisms whose understanding and use in today‘s society are still in their infancy. If we look at the development of plastic, which in just under 100 years has gone from Bakelite to the most versatile material of our time, the potential of fungal organisms can only be guessed at.

Institute

Hochschule für Angewandte Wissenschaft und Kunst HAWK Hildesheim Fakultät Gestaltung

Student

Maurice Lötel

Support

Julia Kuhlenkamp (Werkstattleitung Modellbau)

Bernd Krupp (Werkstattleitung Licht-/ Elektrotechnik)

Supervision

Prof. Dr. Sabine Foraita

Prof. Dr. Manuel Kretzer